By John R. Dockendorf

I never thought I’d be a soccer dad. I always envisioned weekends with my four kids would be spent hiking in the woods, skiing, or mountain biking. Instead, Jane and I spent many years; and dozens of spring, fall, and even winter weekends dividing and conquering as we figured out how to get our four kids to different soccer games in multiple states. These parental challenges are not unique, and I watch many of my younger friends with their middle school children doing the same. Overall, we spent about ten years as soccer parents.

My kids still love soccer, and I applaud the many good things the sport brings. I like the friends my children have made through soccer and their families, friends they still keep up with now that they are in college. I like the conditioning and emphasis on activity and health. I like the camaraderie, focus, and the teamwork they learned, and many of their coaches were inspirational role models. I loved the fact that my girls look up to Tobin Heath and Carli Lloyd instead of Miley Cyrus and Rihanna.

But while soccer is a great activity, I felt it was too much of a good thing. Finding a passion, working hard to attain skills, and being able to measure one’s growth through competition is a great way to build the confidence that will serve one throughout life. But even in middle school we felt pressure from coaches and other parents to focus on soccer exclusively and even to spend the summer at various soccer and college ID camps.

Whether this quest for single-sport specialization is driven by parental dreams of being part of the elite 1 percent of high school athletes who actually go on to play NCAA Division 1 sports—or the even scanter .0008 percent who go onto play professional sports—or simply the lure of an elusive scholarship to beat the skyrocketing costs of college, I felt the pressure to specialize exclusively on a single sport was ultimately not in my kids’ best interest.

The bar has been set ridiculously high for those who wish to excel. Globalization has created a world that rewards the specialists at the expense of the generalists. We can all quote Malcom Gladwell’s statistic that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to be great at anything. And that bar keeps getting raised. The level of play in high school or even middle school sports has never been higher, but has anyone stopped to question if this is ultimately important? Is there any correlation between the actual caliber of play and the life lessons one can learn through sport?

A study of Olympic athletes found that successful athletes grew up in an environment where fun was emphasized over winning until the teenage years. Personality qualities inherent and consistent in medal-winning Olympians were ability to focus, self-confidence, optimism, resiliency, mental toughness, work ethic, and, of course, sports intelligence and natural athleticism. I’ve been fortunate to know several Olympians, and none from my sample size had parents who pushed them. All were incredibly self-motivated, naturally athletic, disciplined, and willing to give up their personal lives in order to pursue Olympic dreams. Few teenagers have this drive or dedication. Only one of my four kids had this level of motivation.

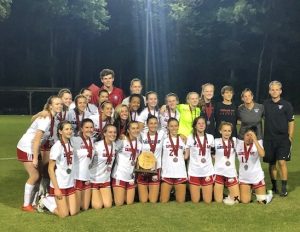

I never expected my kids to play soccer in the World Cup and only one of my four was a college level athlete. COVID ended up killing her chances to play college ball, though she still plays club soccer in college and retains her love for the sport. As parents, we couldn’t have committed more than we did to our daughters soccer and our efforts paled compared to most soccer families we know. of interest, while she still loves soccer, she is equally passionate about mountain biking, pickle ball and skiing and prefers having a a variety of interests and talents.

Even if our kids had the talent and drive. We never saw the end game as worth it. Instead, we hoped to be able to raise well-rounded, balanced kids who would gain competencies in many different areas. If they get asked to do something like go sailing, play bocce ball, or go to a symphony, I will hope they would have at least a working knowledge of each so they could be an eager participant. I want my kids to peak in their 60’s, not their late teens. I hope they won’t look back at their high school sports career as the highlight of their life, but rather just one of many valuable growing experiences that helped prepare them for an engaged life filled with continuous growth.

And if by some miracle, they were to become professional athletes, that would be a cool career with great income potential. And in the big picture, it might give them a platform from which to do good, but would it be the optimal way for them to contribute to the betterment of the world? Sports indeed has a place and my kids have taken much from soccer, but ultimately, it’s only a game.

John R Dockendorf is a hospitality and recreation business consultant based out of Hood River, Oregon and Hendersonville, NC

References:

Changing the Game Project Blog, John O’ Sullivan

Whose Game is it, Anyway? Ginsburg, Durant and Bakltzel

The Most Expensive Game in Town: The Rising Cost of Youth Sports and the Toll on Today’s Families, Mark Hyman

Psychological Characteristics and Their Development in Olympic Champions, Daniel Gould, Kristen Dieffenbach, Aaron Moffett